When I was around 14 years old, casting around for new things to listen to, I found The Nylons 1984 album Seamless in my dad’s record collection. I loved the whole album right away, but I especially loved The Lion Sleeps Tonight. The strange tightrope it walks between haunting and soothing, the melodic howling, the fairytale feel, the plotlessness, the seemingly-nonsense chorus—these things really drew me in. I can’t say for sure that this was the first time I’d heard the song, but it was certainly the first time I’d listened to it. At the time I was so curious how this song came to be, what it was about.

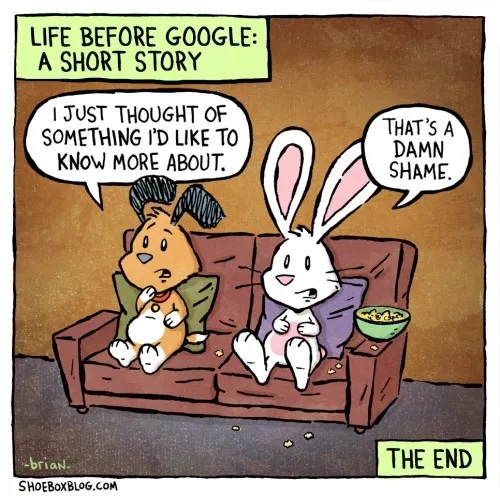

Credit: Brian Gordon

I don’t think younger people can ever really understand this, but of course in the late 80s, we could not satisfy our curiosity about things with a tap on a screen. Tumbling down the Wikipedia hole would not become a thing for 20 more years. So while I was enthralled by this song, I didn’t really know anything about it. I suppose I could have scoured our little hometown library for something, but even if the right book had been housed there (doubtful)—the idea never crossed my mind. So, like so many brief passions throughout my life, I moved on without satisfying my curiosity.

We forget all about these things and then, years later, something triggers the memory, and we realize we now have the world’s knowledge at our fingertips. In this case it was a brief mention of the song in the book But Will You Love Me Tomorrow. I probably thought The Lion Sleeps Tonight was a folksong with a foggy history, attributed to the prolific Unknown. It turns out the origin is well known, and fascinating. It’s a story of transnational folk styles, cultural appropriation, genre-bending, and musical exchange and evolution.

Best of all, since the evolution of the song tracks with modern recorded music history, we can literally hear as the song we know develops over 30 years, passing voice to voice, right before our ears.

1939. The song originates with a South African musician named Solomon Linda. His 1939 improvisational recording Mbube (Zulu for “Lion”) was a hit in South Africa. While this is not The Lion Sleeps Tonight that we know, it is clearly in there. This is apparent throughout, but especially at around the 2:20 mark when we hear the clear germ of the famous melody in the improvised high part. LISTEN.

1949. Pete Seeger (something of a hero of mine) heard the song, and, just like I did, mis-attributed it as traditional. He riffed on it, as he does so well, giving us a 1949 American folk version clearly inspired by the original, and inching closer to the modern classic. He called his version Wimoweh and performed it with The Weavers. In this version we hear the main melody line more clearly, and repeated. And the nonsense phrase “A-wemoweh” is here. But we still have no sleeping lions. LISTEN.

(It’s an aside, but such a great example of the kind of person Pete Seeger was: when he learned the original was not a traditional song, but was actually an original composition, he sent Solomon Linda a check for $1,000 and directed all his future royalties to Linda. Alas, the rest of the American music industry was not so decent, and Linda’s estate didn’t receive its due until 2006, after suing Disney and the American music publisher who held the rights on paper.)

1961. The Lion Sleeps Tonight achieved its modern form in the 1961 recording by The Tokens, which hit #1 on the charts. This version has borrowed the “wimoweh” line and the melody, with added lyrics we all know by American songwriter George David Weiss. LISTEN.

From there it was covered many times, including my beloved version by The Nylons. The Wikipedia article on the song lists around 80 versions through the years, with everybody from Ladysmith Black Mambazo to Chet Atkins and Yma Sumac to ‘N Sync and R.E.M. What a satisfying answer to my childhood curiosity.