I watched Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla on Saturday and I can’t stop thinking about it. To be clear, I’m an unrepentant Coppola fan. Lost in Translation, The Virgin Suicides, and Marie Antoinette are all on my favorite-films short list. So I went into this movie expecting to love every frame. But still I couldn’t stop thinking about it.

Coppola’s filmography has a lot of signatures. Lonely and isolated women. Soft color palettes. Slow pacing. Girls looking out car windows. Feet. And perhaps most notoriously, ambiguous endings. I actually think “ambiguous” is the wrong word. The way I see it, her films just have no punch line, and this bugs some people. The most well known example is Lost in Translation which ends with a whispered exchange between Charlotte and Bob. He leans in and whispers in her ear. We are given no inkling of what he says. And we can just make out her silent response by lip-reading: “Okay.” Some people hate this. “WHAT DID HE SAY?” they ask. But not knowing is the point.

That’s the most famous example, but I think the best example is the ending of one of her less-well-received films, Somewhere. (Less well received according to Rotten Tomatoes anyway. The film is wonderful.) It’s hard to describe the ending of this movie without recounting the whole plot, which I won’t do here. Just watch it. But I remember sitting on my couch after it ended, mentally circling the frail possibilities that did not come to pass.

If I had to diagnose Sofia Coppola I’d say she’s too disciplined a filmmaker for sentimentality, and too hopeful a person for cynicism. And so she finds a delicate line between the two. I don’t know anybody else who does this like her. Our TVs are buzzing with maudlin, and bleeding out the edges with cynicism. But not here. Even in Marie Antoinette, a story who’s ending was spoiled for everyone on earth two hundred and fifty years ago, she is perfectly comfortable leaving the inevitable unstated. To show it is to make the movie about it, and that movie is decidedly not about physical decapitation.

I have this habit of jotting down terse unstructured thoughts as they strike me. A week ago I left myself this note:

Hmm. In a line drawing the line is not the thing. It is the boundary between the thing and the not-thing. The thing itself is not actually drawn.

I can’t remember what I was reading or listening to or watching that made me think about this. It’s not particularly deep, but it is interesting right? I heard a comic artist once praise the economy of Snoopy. A few curving lines conveying so much character. When Schulz drew Snoopy he started with a blank page and a vision. Somewhere on that page, according to his vision, was Snoopy. But he didn’t draw Snoopy. Not really. He found the boundary between the part of the page that is Snoopy and the part of the page that is not, and marked it. (Of course this is literally what it means to draw something. Set it aside.) When I took this note, I found it interesting that we don’t actually pencil in the thing itself. I’m not talking about Magritte here, or at least I don’t think I am. Ignoring what Snoopy really is, just looking at it mechanically, what we put on the page is a line separating Snoopy from the universe. The drawn Snoopy reveals itself, for the most part, in the space between the lines.

I read this note, and it got me thinking about Priscilla again. Coppola’s way of ending things is not really about endings. That is just one type of the greater form that to me really defines her work. And this is what I kept thinking about. In the same way that a line drawing articulates the boundary of a thing and not the thing itself, Coppola’s filmmaking evokes something without explaining it. She has a crystal-clear vision and this immense skill to reveal it to us on screen. She is drawing the boundary between her meaning and not-meaning with a few “simple” lines, and that meaning reveals itself to us in the unstated space. This is certainly not the only way to tell a story, just like line art is not the only way to represent an image. And for all I know, there are countless other filmmakers who do the same thing. I’m not much of a film buff. But in a Snoopy-like way, Coppola’s films have an economy, and it always thrills me.

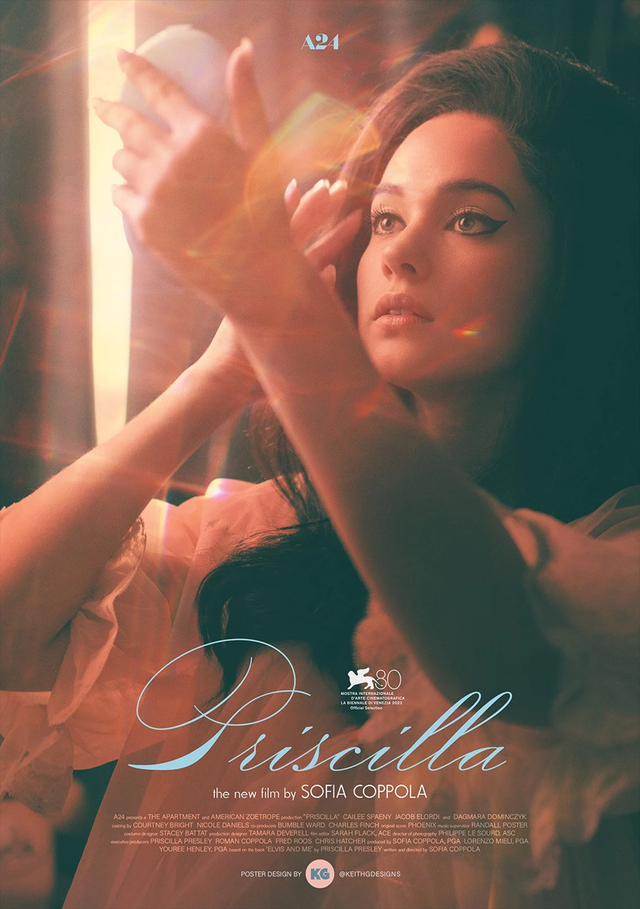

Priscilla is a beautiful movie. Blue to Virgin Suicides’ pink, and languorous like Marie Antoinette. Cailee Spaeny is perfect in what I would have assumed was an impossible task: convincingly playing both a wide-eyed naive 14-year-old girl and a battle-hardened 24-year-old woman.

It has a perfect ending. It is so gentle and soft-spoken, and at the same time triumphant and deeply moving. In a way it subverts a Coppola trope, to great effect. (It is also a small ending, simple and humane. A moment every living person can identify with. I love this kind of thing.) It reminds me of Romeo and Juliet (but with divorce in place of suicide). A young woman let down by family, church, and state, taking the reins of her own life. Just like Juliet, Priscilla takes the reins so discretely you may not even notice she’s done it at first. It is quiet and understated, but there is real heroism there.

(N.B. I don’t mean to imply that suicide is heroic. I think Shakespeare, operating in the Roman tradition, meant it to be. But with classic Shakespearean brilliance, he also meant us to be horrified by it. But what I find heroic is Juliet’s self-actualization—“Go in, and tell my lady I am gone…"—despite the sad and tragic ending she ultimately chose for herself.)

I loved this film. It is a beautifully delineated boundary between the thing and the not-thing. And like all things well told, I can’t tell you what that thing is, any more than I can effectively describe Snoopy to someone who’s never seen him. Coppola tells us what she wants to say in the only way it can be said.